The last opera of Shostakovich

“We thrive on negative criticism, which is fun to write and to read”, thus the great and fictitious restaurant critic Anton Ego in the movie Ratatouille. Every artist, whether a performer or a creator, is acquainted with the sinking feeling of opening the morning newspaper or the website, skimming through the content (the eyes stop on their own at key words), and then the growing realisation that the show, the book, the movie, the exhibition were slaughtered by the critic. But in our everyday experience, whether the artist was offended or not, the entire thing stays within the inter-personal field: as a dialogue between the critic and the artist (with the readers’ crowd for audience). But imagine a cardinally different situation – living under a dictatorship, where art is carefully monitored by the regime, and woe to the artist who treads a path frowned upon by the powers above! In such a case the ramifications of a bad review, especially one that reflects the regime’s opinion, might go much further than just a bruised ego.

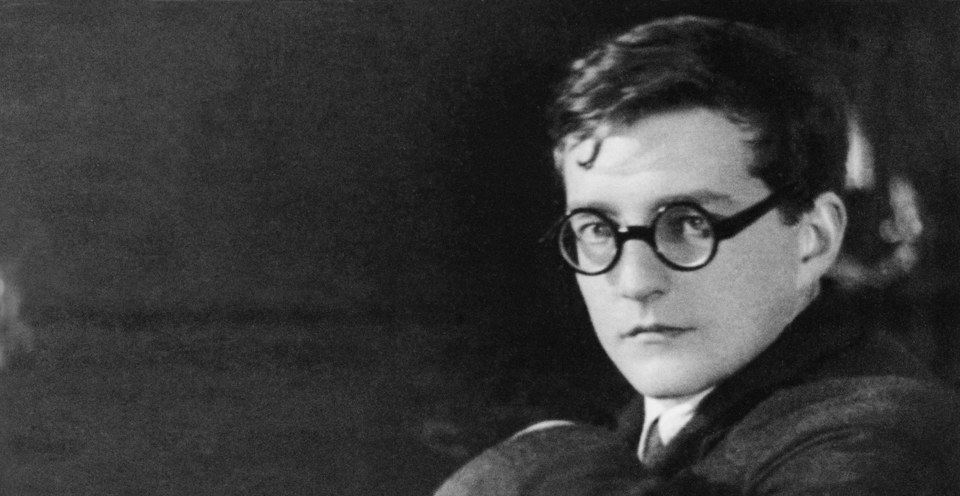

Such was the situation in Soviet Russia in 1936, when Dmitry Shostakovich, the young and well-known composer, bought the Pravda from the 28th of January. Almost at once he stumbled upon an editorial titled Chaos instead of music. The subtitle explained: “about the opera Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District” – an opera which Shostakovich finished composing in 1930 and which was at that time being staged at the Bolshoi, the main opera house of Moscow. And under those titles came the most slaughtering of slaughtering reviews:

“From the first minute, the listener is shocked by deliberate dissonance, by a confused stream of sound. Snatches of melody, the beginnings of a musical phrase, are drowned, emerge again, and disappear in a grinding and squealing roar. To follow this “music” is most difficult; to remember it, impossible… Here is music turned deliberately inside out in order that nothing will be reminiscent of classical opera, or have anything in common with symphonic music or with simple and popular musical language accessible to all… While our critics, including music critics, swear by the name of socialist realism, the stage serves us, in Shostakovich’s creation, the coarsest kind of naturalism… And all this is coarse, primitive and vulgar. The music quacks, grunts, and growls, and suffocates itself in order to express the love scenes as naturalistically as possible. And “love” is smeared all over the opera in the most vulgar manner…” (trans. Victor Seroff)

And it goes on and on – “shrieks”, “cacophony”, “noise”, “nervous, convulsive, and spasmodic music” – the critic didn’t like, to put it mildly (we will return later to the question of that anonymous critic’s identity). But while the quotes above could have – theoretically – appeared in a review dated from our time (with the exception of the “socialist realism”, to which we will also come back), the following lines would have caused greater bewilderment:

“The composer apparently never considered the problem of what the Soviet audience looks for and expects in music. As though deliberately, he scribbles down his music, confusing all the sounds in such a way that his music would reach only the effete “formalists” who had lost all their wholesome taste. He ignored the demands of Soviet culture… …[this] carries into the theatre and into music the most negative features of “Meyerholdism” infinitely multiplied… The danger of this trend to Soviet music is clear. Leftist distortion in opera stems from the same source as Leftist distortion in painting, poetry, teaching, and science. Here we have “leftist” confusion instead of natural human music. The power of good music to infect the masses has been sacrificed to a petty-bourgeois, “formalist” attempt to create originality through cheap clowning…

These paragraphs read as a political, rather than an aesthetic accusation, and were more dangerous by far. This is hard for us to grasp – why was the music expected to be… anything at all? Shouldn’t every artist create whatever stems from his own talent and his own inner world? And shouldn’t Art be judged only upon its own artistic faults and virtues?

To understand this, one must explain the official stand on art in the Soviet Union. “Art belongs to the people”, proclaimed Lenin, and as such art was bound to serve the people to whom it belonged (this, of course, was only a slogan; in reality, art “belonged” to those who had the power to permit or to prohibit the publication of a written text, the staging of a play or the filming of a movie – the Communist Party and those leading it). Art had to be catchy, simple, clear and accessible to all. In the 20’s there was still place in the Soviet Union for a multi-voiced artistic discourse, including, among others, avant-guard theatre, abstract painting, symbolist and nonsense poetry. But since the early 30’s, together with the ongoing struggle against the “enemies” within the Party (i.e. opposition, real or staged), the regime started severely censuring every art movement which strayed from the artistic ideology proscribed by the state – that selfsame socialist realism, by the name of which the music critics swore.

What was this strange beast? The official definition was given in 1934 at the first congress of the USSR Writers’ Union. An artist creating according to the principles of the socialist realism was expected to offer a “truthful, historically concrete representation of reality in its revolutionary development. Moreover, the truthfulness and historical concreteness of the artistic representation of reality must be linked with the task of ideological transformation and education of workers in the spirit of socialism.” Couldn’t be clearer, could it? What it meant was that the artist was expected to stick to the truth, but only to that truth which suited the “ideological transformation” led by the Party. In addition, the demands for simplicity, clarity, accessibility were preserved – they were all united under the affable word narodnost’ – which can be loosely translated as “folksiness”.

Formalism, of which the opera was accused, was the embodiment of all things contrary to those demands. The historical roots of the definition relate to an artistic concept according to which form supersedes content in importance. But in the Soviet Union of the 30’s the term became an ideological cliche, and was applied to every work of art which was perceived as being “elitist”, and as such distanced from the people and from the demands of the socialist realism.

Shostakovich himself had been previously accused of being a formalist, including for Lady Macbeth, but had heretofore always defended himself bravely. In April 1935 he wrote in the newspaper Izvestia: “In the past I was harshly condemned by the critics, first and foremost for formalism. I categorically refused to accept those accusations and will not accept them. I never was and never will be a formalist. Slandering a work as formalist only because its language is complex, or because it is not immediately apparent, is an impermissible recklessness.” Responding in such a way at those times was an admirable feat of bravery and artistic integrity.

But now there was no one to respond to. The review was published anonymously – as an editorial – at the official Party newspaper. Herein lied the danger: such accusations, in particular when they came from such a source, were reason enough for artistic blacklisting, public persecution, and in extreme cases for arrest, exile and even death. One needn’t look far to find an example: Vsevolod Meyerhold, who was mentioned by the critic (Shostakovich, according to him, brought “Meyerholdian” traits into the opera), was one of the greatest theatre directors of Russia. After the October Revolution he applied himself excitedly to the Socialist cause, and in the 20’s even enjoyed the regime’s plaudits. But towards the 30’s, a change in his artistic attitude led his plays to become increasingly abstract, grotesque and bitterly satirical. Those changes distanced him from the party’s line, and caused an unending stream of accusations of formalism. His art was denounced as foreign to the people and hostile to the realities of Soviet life. His end was tragic. In 1938 his theatre was shut down. A year later he was arrested, interrogated, and under harsh torture made to “confess” to betraying his motherland and spying for the “capitalist enemy”: the British and the Japanese. In 1940 he was executed by firing squad. Prior to that, near the time of his arrest, his wife, the actress Zinaida Reich, was murdered in their apartment by multiple knife stabs. They were not the only ones – in those years (and in fact, all through the existence of the Soviet regime), there was not a single person in the Soviet Union who could vouch for his own safety, the safety of his family or at least for his working place. Nothing granted protection from the regime – neither one’s position in the Party, nor one’s previous achievements, and certainly not one’s artistic talent. Therefore, the following sentence from the review reads especially dark and threatening: “It is a game of clever ingenuity that may end very badly.”

Some of you might now be curious to know what happened in the opera, and what this formalistic monstrosity sounded like. To start with, a few words about the plot: Katerina, a young woman, is married since five years to the merchant Zinovij Izmailov. Loveless and without children, Katerina is ready to claw walls out of endless boredom and sexual yearning:

“…but no one will come to me, no one will put his hand round my waist, no one will press his lips to mine. No one will stroke my white breast, no one will tire me out with his passionate embraces.”

Her husband lacks a backbone, and his old father, Boris, rules over house and trade with an iron fist. The merchant Zinovij departs the house – a dam has been breached, and his presence is necessary – and before leaving presents a new labourer, Sergey, handsome and arrogant, of whom the rumours whisper: was thrown out of his previous master’s house for getting involved in an affair with the mistress herself. Katerina encounters him chasing the cook in the head of a group of trade workers (today this scene is often staged as a gang rape), and their quarrel, which includes a bit of manhandling, excites him so strongly that he sneaks up to her room that night, to “borrow a book”. Books she has none: she herself is illiterate, and her husband doesn’t read books – but their conversation, which at first concerns Katerina’s bitter fate and Sergey’s “sensitive” soul, soon slides onto other rails. Sergey overcomes Katerina’s resistance (she is torn between her yearning for Sergey and the vow of chastity she had sworn to her husband) and carries her to the marital bed, accompanied by some very graphical music indeed (in 1935, the New York Sun critic dubbed it “pornophony”, which, one must admit, is pretty close to the truth).

Sergey is not the only one wishing for Katerina’s company. Her father-in-law, Boris, walks around the courtyard with a lantern, lurking for thieves, and upon seeing the light in Katerina’s window, decides to visit her too:

“Seems she can’t sleep; of course, she’s a young woman; hot-blooded too and there’s no one to console her. Ah! Now if I were younger, just ten years or so, what I’d do! She’d have it hot from me; hot, yes, by God, so hot, it’d even be good enough for her! A healthy woman like that and no man around, no man, no man, no man , no man, no man around; no man, no man at all. No man, no man, no man, no man; it’s dull for a woman without a man, I’ll go and see her, yes I will!”

But too late – he hears the lovers part, realises right away what was going on (“You’re too late, Boris Timofeyevich!”), and rushes to catch Sergey as he climbs down the drainpipe. The punishment: 500 lashes given by his own hand, and all the while Katerina cries in supplication and hate and struggles against the labourers who hold her. When Sergey faints and the rest of the punishment is postponed to the following day (“We can’t do too much at once, or he’ll peg out.”), Boris, hungry and tired, orders Katerina to bring him food. She brings some mushroom – leftovers from dinner – which please him a great deal (“They’re delicious mushrooms, you’re really an expert, Katerina, at preparing mushrooms”). But they soon seem to accord with him less: Katerina had put rat poison in his dish. Suffering terribly Boris Timofeyevich dies, and is buried.

Katerina’s husband hasn’t returned yet, the father-in-law is done away with, and she enjoys a short spell of happiness (“Kiss me!…Not like that, not like that; kiss me so it hurts my lips and the blood rushes to my head and the icons fall from their shelves”). But Sergey refuses to cooperate. He is “not like other men, who don’t care about anything, so long as they’ve got a woman’s soft body to caress.” How can he, with his “sensitive soul”, see Katerina go to bed with her lawful husband? She calms him – “that won’t happen”. And indeed it doesn’t. One night her husband returns, accuses Katerina of cheating (“Everything, everything we’ve heard about your affairs, everything, everything), struggles with her, she calls Sergey to protect her, and together they overpower Zinovij and strangle him. “Get a priest…”, gurgles Zinovij, as Sergey lets go for a moment. “I’ll give you a priest all right!” answers Sergey, and hits Zinovij over the head with a heavy candlestick. After the deed, Sergey drags the body into the basement by the light of Katerina’s candle, and hides it there. “Now you are my husband”, says Katerina.

But their joy doesn’t last for long. On their wedding day, a “shabby little man”, as he is called in the libretto, sneaks into the basement, looking for a bottle or two of vodka, and discovers the body. Terrified, he runs to the police. The accompanying music, however, radiates pure schadenfreude and even a kind of grotesque happiness derived from the entire affair. The singer Galina Vishnevskaya, one of the greatest interpreters of Katerina’s role, recalls in her memoir “Galina: the story of a life” (1991), that Shostakovich used to say about this scene: “to the police he runs, the bastard – delighted he is going to inform… a hymn to the informers… it’s a hymn to all the informers!”

At home, during the wedding feast, Katerina notices the open basement door, and full of real terror, entreats Sergey to leave everything and run away. But too late – the polices already knocks at the gate (“You didn’t invite us, but here we are anyway! A little matter has arisen!…. There’s a little matter of a certain kind, to put it bluntly, a matter!”). Katerina gives herself up, Sergey tries to resist arrest but in vain. They are sentenced to a public flogging and exile to Siberia.

On the long and hard road to Siberia, Sergey’s “sensitive” soul tires of Katerina and he begins to woo another beautiful and young woman – Sonetka. She, on the other hand, feels no rush to oblige by granting him “his heart’s desire”, and demands a proof of his love. And what proof? Her stocking are torn, and she is cold. Let him get her another pair. Sergey exploits Katerina’s unwavering love for him and obtains the stockings, seemingly for himself. When Katerina sees her stocking on Sonetka’s legs, all becomes clear to her. And Sonetka even mocks her:

“Thank you, Katerina Lvovna, thank you, Katerina Lvovna, thank you for the stockings! Look how fine they look. on my legs. Seryozha put them on for me. and kissed my legs to make them warm! Oh, Seryozha, my Seryozha, Katerina’s a fool, she couldn’t keep Sergey. Ha, what a fool! Ha, what a fool! And you won’t see your stockings again. They’re mine now, look! I’m warm now!”

Katerina doesn’t say a word. After a few moments, when she sees Sonetka standing on the edge of a cliff and looking down, she slowly approaches her, grabs her in her arms and together with her jumps into the foaming waters. End.

Indeed, this is no pleasant or easy entertainment. But what those paragraphs cannot convey is the boundless emotional power of the music that accompanies those rather horrible events. Like a mighty river flow, the tension doesn’t ease up from Katerina’s entry aria till the last knock of the timpani and the shouting chord that ends the opera. And all that time the music reflects not only the transpiring events, but first and foremost the feelings of the participants. Shostakovich distills the most basic feelings: fear, desperation, hate – but also passion, love, hope for happiness – and pours them into an aural picture projected to us, the listeners.

It is as if he broke the unspoken theatrical conventions, and instead of presenting us with theatrical feelings, penetrated deep into the tangible life with a might which permits no indifference on the listener’s part: under the music’s sway the listener is bound to feel. The effect is almost scary in its strength, and therein lies, in my opinion, a large part of the opera’s psychological power.

Luckily one can find online the Soviet musical film which was based on the opera, made in 1966, in its entirety:

This is based on a shortened and edited version of the score, but among the existing recordings, I feel it’s hard to find another one so true to the spirit of the work, and which can boast of such a musical cast. (Moreover, it seems to me that the opera benefits from its very being filmed: the acting and the editing enhance the music a lot). Galina Vishnevskaya, whom I mentioned above, is the only one to both sing and act in the movie – the rest of the participants are movie actors, who “sing” in lip-sync with the singers.

I can warmly recommend watching the entire movie, but here’s a shortlist of the strongest moments: Sergey’s being flogged by Boris (41:25), the poisoning of Boris (44:53); Zinovij return and death (1:05:04); the scene with the shabby little man (1:11:06, and especially the orchestral interlude at 1:14:00); the song of the exiled to Siberia (1:22:49 – “O, you, road ploughed by chains, / the road to Siberia, sown with bones, / this road has been watered with blood and sweat, / death groans arise from it…”); the purest, most lyrical moment of the opera – Katerina’s words to Sergey as they meet after a day’s march (1:29:12 – “Seryozha, my dearest! At last! I’ve gone the whole day without seeing you, Seryozha! Even the pain in my legs has gone, and the tiredness, and the grief, now you are with me…”). And finally, her final monologue, terrible in its disconnectedness, after Sergey’s betrayal, as for the first time since the opera began she understands what she’d done, and we see the dark chasm yawning before her (1:38:10):

“In the wood, right in a grove, there is a lake, almost round and very deep and the water in it is black, black like my conscience. And when the wind blows in the wood, on the lake waves rise up, huge waves and then it’s frightening, in autumn there are always waves on the lake and the water’s black and the waves huge. Huge, black waves…”.

Who then wrote the review in the Pravda? And why did it only appear two years after the opera’s premiere – when the opera had already seen more than 170 performances in Moscow and Leningrad (to say nothing about premieres in London, New York, Zurich, Stockholm, Buenos Aires et al)? And what of all the previous reviews in the Soviet press, which were nothing but stellar: “the first classical Soviet opera”, “a great victory of the Soviet music”…?

The archive information points to David Zaslavsky as being the review’s author. Zaslavsky (1879-1965) was a talented yet unscrupulous journalist, who changed political sides whenever it was worth his while. A Menshevik during the revolution, he joined forces with the Bolsheviks thereafter, and took part, among others, in the persecutions of the poets Ossip Mandelshtam and Boris Pasternak (two stories that ended badly: Mandelshtam was exiled to Siberia in 1938, but died of illness before reaching it – even though one did not walk that way anymore, it still remained “sown with bones”. Pasternak died of lung cancer in 1960, two years after the prolonged persecutions in the media and the heavy social pressure made him decline the Nobel Prize in literature).

But the question is, did Zaslavky write the review on his own, or was he acting upon orders from above? Here we enter an area of speculations, but it’s hard not to connect the review’s appearance with Stalin and his entourage visiting the Bolshoi and seeing the opera two days before that, on the 26th of January 1936. Stalin loved opera, frequented the Bolshoi and even had favourites among the singers. But all evidence agrees that he loved melodic, easy to follow tunes, loved the Russian operas of the 19th century – Prince Igor, The Queen of Spades, Ivan Susanin – as well as folk music.

Moreover – he did not tolerate any kind of unbecoming behaviour or attire. Vishnevskaya, the singer, recalls in her book how disgusted Stalin became seeing Tatyana in a light morning gown in the last scene of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin – a scene, in which according to Pushkin she is “sitting peaked and wan, / alone, with no adornment on;” (trans. C. Johnston).

Seeing her thus unadorned, with Onegin before her, Stalin cried: “how can a woman appear before a man like this?!” And since that day, writes Vishnevskaya, Tatyana always wore a heavy velvet dress in that scene, her hair arranged for an evening ball – and to the devil with Pushkin.

And now Stalin was presented with Lady Macbeth, with its piercing, strident musical language, light years away from Tchaikovsky’s nobility or Borodin’s colourful folk-like melodies – Shostakovich’s music was soaked with passion and lust, full of explicitly sexual scenes. It’s not surprising to discover that Stalin left the theatre before the final act, infuriated.

In juxtaposition to Stalin’s personal tastes, Solomon Volkov, author of Shostakovich and Stalin: the artist and the Tsar (2004), presents a line of political reasoning to explain Stalin’s reaction to the opera. Stalin, writes Volkov, was at the time leading a wide anti-formalistic campaign in all the arts; the Pravda was publishing one anti-formalistic article after the other – against formalism in cinematography (13th of February, 1936), in architecture (Feb 20th), in painting (March 1st), in the theatre (March 9th). The review of Lady Macbeth becomes in such an analysis a single link of a bigger chain: the regime needed an appropriate negative example in the field of music, and Lady Macbeth fit the bill. From the ethical point of view as well, continues Volkov, the opera did not agree with the line led by the Party at that time – the agenda was strengthening the institute of the Soviet family: obstacles were being put before those who wanted to divorce; abortions were outlawed, and photographs of Stalin with young kids were often published in newspapers. And here came an opera lauding “free love” (or as the critic put it, “a glorification of the merchants’ lust”), in which the divorce problem is solved simply and brutally – by killing the hated husband.

The combination of those two reasons can possibly explain the double-edged nature of the review’s accusations: aesthetic on one side (“a confused stream of sound”), and political on the other (Shostakovich “ignored the demands of Soviet culture”). But whether the hit came from here or from there, after the review was published, the days of Lady Macbeth on the stage of the Bolshoi were counted – the run was closed down after just three more performances. Within less than a month the composers of Moscow and Leningrad published condemning resolutions, and the opera was stricken out of the repertoire of the Soviet theatres till 1962, when it was staged again in a second, shortened and edited version, created by Shostakovich in 1955 (this is the version upon which the movie mentioned above was made).

Shostakovich, as opposed to many other in that era, was not arrested, was not exiled, was not executed, his immediate family remained unharmed. In the creative field, we, as observers from the future, can too say that he came out victorious – his next large-scale symphonic work, which was called “a Soviet artist’s creative response to justified criticism” (i.e, one which was seen by the regime as Shostakovich’s agreement to compose within the limits set by the Party), was his Fifth Symphony – one of the pinnacles of the symphonic composition of the 20th century, and perhaps Shostakovich’s most popular work in concert halls today.

His following relationship with the Soviet government followed the carrot and stick approach – though one must admit that in Shostakovich’s case the number of carrots exceeded the norm – five Stalin prizes, five orders of Lenin and one Lenin prize, Hero of Socialist Labour, order of the October Revolution, USSR State prize and many others. The stick, when it came, was just one but very heavy. In 1948, Shostakovich topped the list of the composers accused of formalism and of distancing themselves from the people. The vast majority of his works were blacklisted, he was fired from the Moscow Conservatory, all his privileges and those of his family were rescinded, and till Stalin’s death in 1953 he was forced make a living out of writing film music (work which he hated) and a few pro-Party pieces. The public condemnation and the persecutions in the media need not be mentioned – those were self-evident.

The cynics will say – so what, even then he wasn’t arrested, he wasn’t exiled, he wasn’t executed. He survived in a place where millions perished. But it seems to me that there was a price to pay for the ongoing fear for himself and for his family, for the public insults, for the need to constantly lie and pretend, both in his outward appearance and sayings and in his “state” compositions: all of those left their mark in his “real”, sincere music – starting with the Fifth Symphony, that “creative response to justified criticism”, through his Second Trio, his Eighth and Tenth Symphonies, the Eighth Quartet (which, according to his children, he composed in memory of himself); and till his last works – the 14th Symphony (a symphonic cycle of death-related songs), the 15th Quartet (a string of six Adagio movements, including a funeral march and an elegy); the cycle of songs to the Sonnets of Michelangelo, and his very last composition, the Viola and Piano sonata. I think one need not be a student of history of music or even be acquainted with the circumstances of his life to hear the boundless pain in these works, the brokenness and the blazing anger. And at the same time – the freezing, the static blankness of having no choice and no escape. And since Lady Macbeth, despite numerous proclamations regarding his future creative plans, he never wrote another opera.