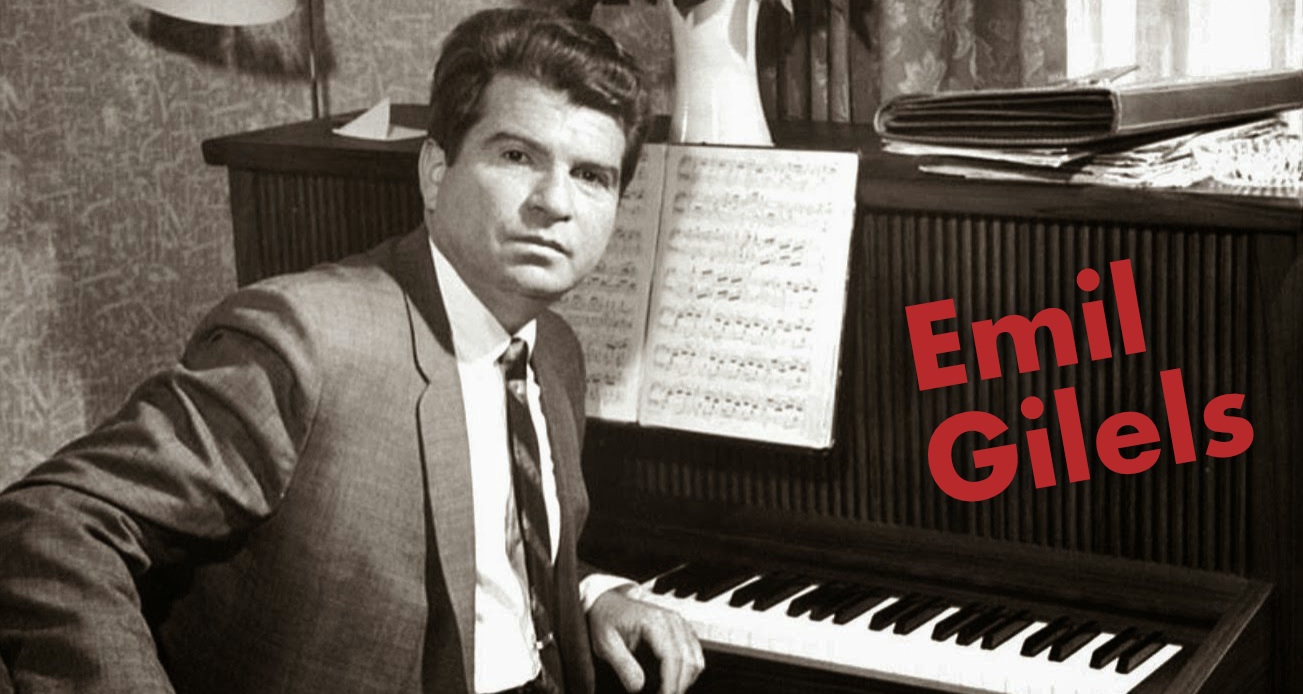

Emil Gilels

(I originally wrote this article for the October 2017 issue of Gramophone magazine. This is a modified, extended version.)

Emil Gilels (1916-85) has always been a personal hero for me. Without gimmicks or eccentricity, the all-encompassing warmth and deep humanity of his recordings strongly attracted me, and my admiration grew steadily as I discovered more of his discography. The Gilels I knew – the noble, poetic, profoundly serious musician – was, it turned out, just one side of him, that which was more readily apparent in his later-life recordings. The earlier recordings he made in the 1930s revealed a different interpreter. You can hear a fiery, fearless virtuoso, already noble in his sound, already on the search for the core of the music he was performing, but one, if I may say so, yet unencumbered by wisdom, with freshness and daring balancing his innate refinement and immaculate musical taste.

All these recordings are available online. Here are three of them, as a small selection: short pieces by Rameau, Loeillet and Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody No. 9:

Polished, unostentatious virtuosity in the Liszt, and what wonderful, natural musicality in the Rameau. This was the time of his first two major breakthroughs: winning, as a hitherto unknown 16-year-old from Odessa, the first All-Union Performers’ Competition in 1933 in Moscow; and winning the Ysaÿe Competition in Brussels five years later – the one which was to become the Queen Elisabeth Competition, and among whose winners were David Oistrakh, Leon Fleisher, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Vadim Repin. The first win brought fame in the Soviet Union, the second marked the beginning of international fame, which was curtailed by the Second World War and had to wait until the 1950s and ’60s to reach its zenith.

Some of his greatest performances come from those two decades. Of these, Saint-Saëns’s Second Piano Concerto with Cluytens is a masterpiece, with a tragic, artless narrative in the first movement; nuanced, delightfully elfin virtuosity in the second; and a veritable avalanche of sound in the finale which is dangerous, gripping and utterly thrilling:

My other favourites include Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto with Ludwig and the Philharmonia Orchestra, and Chopin No. 1 with Kondrashin; this live version of the Chopin is much superior to the studio recording with Ormandy, which is relaxed and even somewhat stately, while the former breathes, full of tangible emotion, with painfully beautiful phrasing in the first and second movements.

A lesser-known, but thoroughly absorbing recording is the G minor sonata by Nikolai Medtner, sweeping and dark. Medtner, a contemporary (and close friend) of Rachmaninov, had also emigrated from the Soviet Union, and his music was blacklisted there for many years. After Stalin's death, Gilels was the first to perform Medtner again:

Gilels was a passionate chamber musician, and in the 1950s he formed a very active trio with Leonid Kogan and Mstislav Rostropovich. Their rendition of the Archduke Trio is legendary, but I’m repeatedly won over by their haunting interpretation of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Trio, as well as by the Tchaikovsky A minor Trio, which is heartfelt, lyrical and impassioned without a shred of mawkishness.

I must mention Gilels’s sound, ‘golden’ as it has often been called. His rich, full-bodied tone, always weighted and grounded, could become earthy or monotonous, if not for that lovely gleam that caps every single note, bell-like and clear. Gilels said how important it was to him for every note to speak, and this, he said, often dictated his choice of tempos. But just listen to his Liszt (‘La campanella’, the Spanish Rhapsody, any of the Hungarian Rhapsodies or, indeed, the B minor Sonata), and this combination of weight and gleam is present in every single note of the fastest figurations, which he is also able to imbue with directionality and musical content – a breathtaking effect.

His rhythm immediately commands attention, too. Though flexible, it’s mainly characterised by an inexorable pull forward, like being caught in the flow of a great river. The effect is often hypnotic: in Shostakovich’s Second Sonata, in his numerous Prokofiev recordings (in particular the Third Concerto), and in the shimmering piano arrangement of Debussy’s ‘Fêtes’:

In the 1970s and ’80s Gilels recorded for Deutsche Grammophon, a collaboration which resulted in a series of gems: Grieg’s Lyric Pieces, tender, sincere and touching; Brahms’s Piano Quartet No. 1 with the Amadeus Quartet (listen for the inspired poetry in the third movement and the exciting, driven finale played with daredevil abandon), as well as the two concertos with the Berlin Philharmonic and Eugen Jochum. Of these, No. 2 is still unsurpassed in its breadth of vision and humanity; the tempo flexibility, sorely lacking in Gilels’s earlier recording with Reiner, grants it a powerful emotional impact, and the poetry of the slow movement is once again breathtaking.

Gilels was also one of the greatest Beethoven interpreters of his time and it’s truly unfortunate that a planned set of all 32 sonatas on Deutsche Grammophon remained incomplete at the time of his death, with five sonatas missing. But I’ll admit that, for me, the studio versions were often surpassed by his many live recordings of the same works. This is the case not only with Beethoven, but also with Schumann’s First Sonata, Liszt’s B minor Sonata, Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto and so on. On stage, Gilels’s playing was full of ‘high-voltage’ electricity, possessed of an inner tension and an immediacy gripping and captivating, allowing no escape. His artistry, so humane and warm-hearted, seemed to thrive on the contact with an audience and became intensified by the lack of a safety net. Luckily for us, many of his concerts were recorded and filmed; I will finish the article with two of many standout recitals – from 1971 in Ossiach, Austria (Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann and Mendelssohn), and from 1978 in Moscow (Beethoven, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov and Scriabin). Both seem to pass in a single, concentrated breath, and to spend 90 minutes in the company of Gilels remains one of my strongest, most memorable and satisfying musical experiences.