Beethoven...

(I wrote this article for the International Piano magazine)

Beethoven is not an easy composer for any instrument, and I remember struggling as a kid with his finger-breaking piano writing, with the seemingly stringent demands of articulation, pedalling, dynamics and tempo. Nonetheless, ever since I began to have some say about repertoire, I wanted to include Beethoven in every recital programme. I was driven by a kind of hunger, stubbornly, sometimes blindly trying to grasp the music, even when I felt that I couldn’t do it justice at the time. It was as if I, or my soul, needed that contact with Beethoven, that life-affirming, purifying charge contained in so much of his music. I cherished every minute I could spend with Op. 101 (‘Holy ground for every musical person’, wrote the great German critic Joachim Kaiser, and I agree unreservedly); I was thrilled before every performance of the Appassionata; and I still remember beaming with elation when I could finally play the Emperor Concerto with orchestra for the first time.

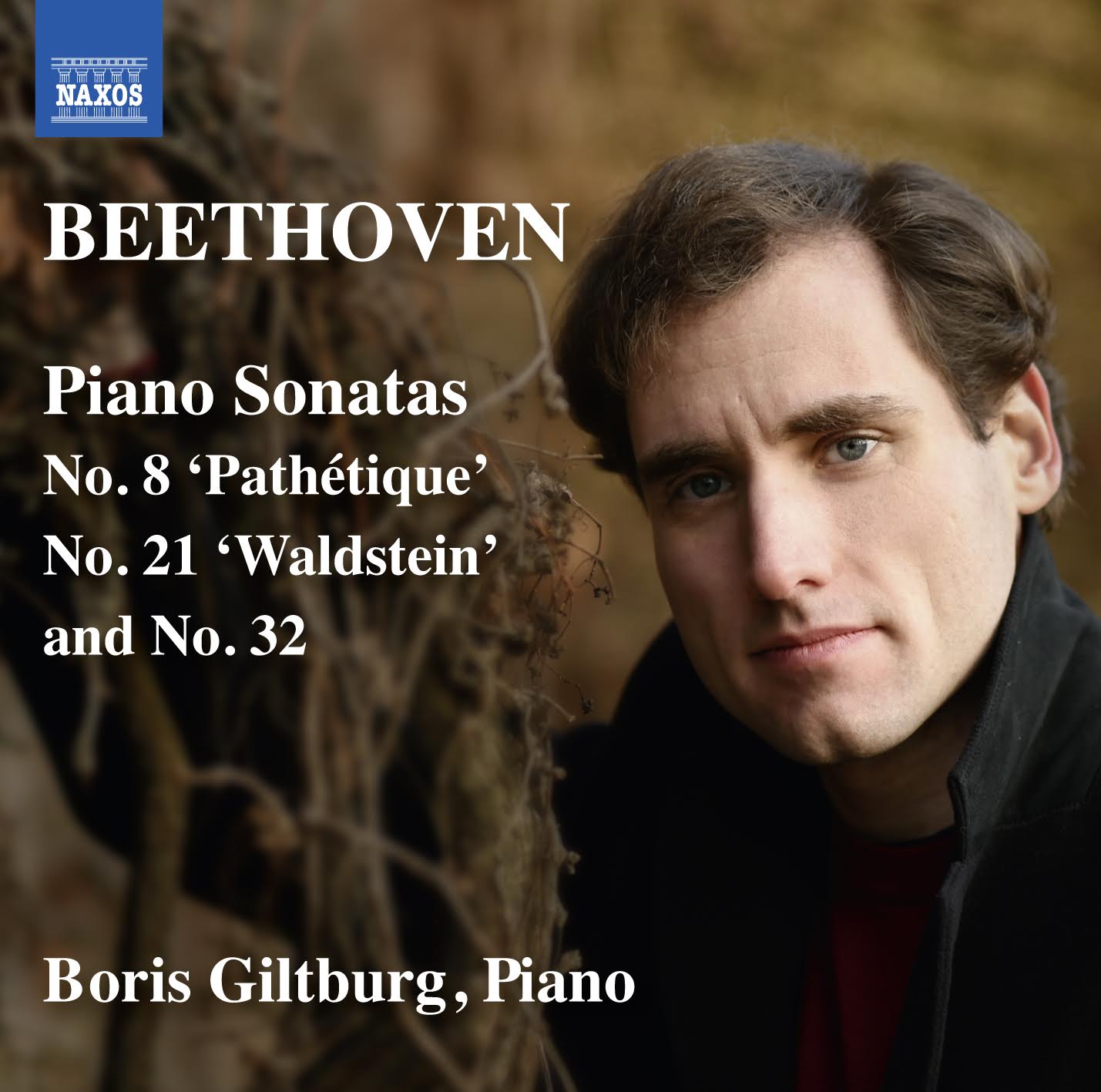

Then came the scary and exciting idea of recording a disc of Beethoven sonatas. The selection snapped into place almost of its own accord: Pathétique, Waldstein and Op. 111, the last sonata Beethoven wrote for the piano. They corresponded to the three semi-official periods of Beethoven’s life and, moreover, were united by their keys: C minor, the emblematic Beethoven key, with its stormy, dramatic, relentless drive; and C major, ranging from blazing brilliance to all-encompassing depth in Beethoven’s hands. What incredible music! I rang Andrew Keener, my producer, in sheer excitement. ‘Oh, that’s brave!’ he said upon hearing the list – which cooled my enthusiasm for a little while. It soon sprang back again, though, and several months later, after an all-Beethoven run-in recital tour, we found ourselves in Wyastone Leys for the recording sessions.

The recording process is in many ways one of crystallisation. The 100 per cent focus maintained for 11 hours a day makes you re-examine decisions which previously seemed obvious, or which would spontaneously occur during a live performance. Vagueness becomes intolerable, and while not everything needs to be spelt out, when things don’t work, you often can’t advance without pinpointing what is wrong and thinking how to fix it. The flow of the second movement of Op 111 was an example of this – usually establishing itself organically in concert, it stubbornly refused to happen on that day. After many tries we realised it was not the tempo, nor the phrasing, no metaphysical idea, but the pulse that was responsible: a tranquil, deep beat, flexible enough to allow the melody its freedom and yet completely unstoppable, like the flow of a great river, or a very slowly beating heart.

During recording sessions, without audience, adrenaline is sometimes missing, so repeatedly trying to invoke the anxiety and near-despair in the outer movements of the Pathétique can bring you to the verge of despair (whereupon it finally translates to the music). This environment, however, also allows you numerous attempts at the finale of Waldstein, trying to capture the true poetic beauty of the opening melody above the unhurried flow of semiquavers in the middle voice.

Over three days in the recording studio, I had the growing realisation that whatever boundaries I had perceived in the music existed only in my imagination. The music allowed complete freedom, and the emotions that Beethoven was trying to convey were as visceral and immediate as anything we might feel today. They were not remotely dimmed over the course of two centuries, nor from belonging to a particular musical style, with whatever preconceptions we might impose on it.

Looking back, my most potent memory from these sessions was the second movement of Op 111, with its breathtaking complexity and depth, its simultaneous intimacy and universality. There is a moment just before its end, after all farewells seem to have been said, when the music climbs up, reaching for the briefest of moments the high C. It is the highest note of the movement, the highest on Beethoven’s keyboard, and has not yet appeared even once in the movement. I never know whether to attribute importance, or indeed premeditation, to such statistics, but coming at the very end it seems to me to stand for something transcendent, which we, having made the arduous, transforming journey are capable of touching, but never of holding permanently.

This, for me, symbolises the movement itself – its truths both profoundly (and alluringly) simple and tantalisingly elusive. I believe it can never be held or known – not really, not fully. One derives tremendous satisfaction from travelling the paths, particularly if at a certain performance, or indeed during a recording session, a small glimpse of these truths can be gained. Yet more always remains to be discovered: it is an endless quest; a life’s-worth of soul-enriching searching.

More details on the CD itself are available here