A Frenchman in New York – Part 1

A listening guide to Ravel's Piano Concerto in G

Hello everybody!

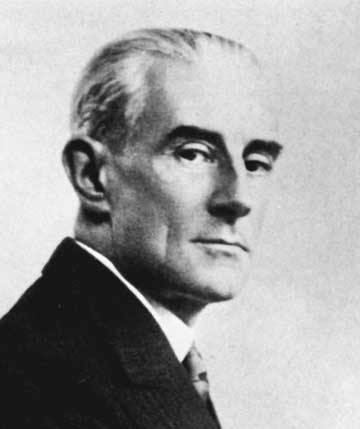

Today’s post, as the titles suggests, will be a brief listening guide to Maurice Ravel’s (1875-1937) Piano Concerto in G. Ravel wrote the concerto in 1929-1931 following an in- and ex-tensive tour of the States in January-April 1928. The tour was a big success, and he felt invigorated rather than exhausted by the experience (saying “it’s incredible how rejuvenated I am”). His fascination with jazz (“Personally I find jazz most interesting: the rhythms, the way the melodies are handled, the melodies themselves”) received a further boost during the tour, as he visited New Orleans with its jazz scene, and while in New York went to hear jazz in Harlem together with George Gershwin. Whether any of this had a direct influence on the concerto is a guess of course, but the concerto is very jazzy at times – rhythm and texture mostly, though there are a few conspicuous melodies too. But as with all great composers, the personal musical stamp is always present – even when it’s jazz, it’s jazz Ravel-style.

From a performer’s point of view, the concerto is a sheer joy to play – the first and third movements are exuberant, energetic, fun and quirky, light fingered, and at the same time have those moments of melancholy which are Ravel’s trademark (and – it’s a secret, don’t tell – these two movements are not terribly difficult). And then there’s the second movement… but we’ll get there tomorrow.

I didn’t like to listen to the concerto as a child – it seemed a total mess, I could never figure out what was going on there, I didn’t connect with any of the melodies, and the second movement was impossibly long-winded and boring (though even then I felt that magic of that wonderful moment towards the end of the 2nd movement when, like a sudden ray of moonlight, the major key appears), But working on it now I was (and am) enjoying myself so much, that it seemed to me prime material for a listening guide – a work which one could enjoy more if one was acquainted with its structure and inner mechanism. So, here we are. I won’t go into such a level of detail as I did with the Mozart or the Bach – we won’t finish it this year otherwise! – but I will try to outline the structure – melodies, sections, etc – as well as comment on the orchestration and piano technique. (edit: nonsense. See the length of the post below.)

There is a whole lot of good recordings of the concerto on YouTube, but as Martha Argerich’s live recording with Temirkanov from Stockholm in 2009 was taken down (this would have been my first choice), I’ll go with her recording with Claudio Abbado on DG, which is currently online.

Here’s the first movement:

27:14 – to let us know we’re in fun/quirky/unusual territories, the concerto begins with a single whip-crack (nothing like a whip to catch your attention – where’s the mosquito?)

27:15-27:29 – the main theme of the concerto, played on the piccolo and accompanied by the piano and the strings (and a bit of snare drum and triangle). All the adjectives I used to describe the outer movements above – energetic, light fingered, fun, etc – apply to this melody, and in addition, it’s nearly pentatonic (meaning it mostly uses only five out of the seven notes of the scale – like Chinese music; I say ‘nearly’ as the melody does include a few occurrences of the sixth note – but still, Ravel creates a specific, slightly exotic sound-scape right from the beginning). The piano is playing figurations, and a very cool thing is going on there: the two hands are both playing simple arpeggios – but in different keys! This, too, contributes to the quirky sound. The strings help with syncopated pizzicatos (a technique of playing whereby the musicians pluck the strings with their fingers – a bit like playing the guitar – instead of using the bow).

27:29-27:38 – a transition passage. A new, syncopated rhythm is added and repeated several times, each time with more instruments and more volume. The piano is playing glissandos – slides up and down the keyboard. A nice idiosyncratic touch – the transition section is 9 bars long (8 is the most common length of a simple musical phrase), so instead of the predictable 2+2+2+2, we get 2+2+3+2 – and as a consequence the piano player has to drag out one of the glissandi (that’s the correct way of saying glissandos) for an extra bar – nothing important, just a small behind-the-scenes thing. As we progress with the transition, the tension keeps and keeps mounting, by the end of it the whole orchestra is playing and we finally arrive into –

27:38-27:57 – a full repeat of the main theme, played by the trumpet and accompanied by honk-like sounds from the horns and trombones and by pizzicati from the strings (and the harp, but it’s not really audible behind the much harsher sound of the brass; I do wonder though if the sound would be different were the harp not playing – might well be). The whistles at 27:46-27:49 are done by the piccolo together with the triangle. The strings take over at 27:50, adding much body to the sound (the brass was loud, but not earthy – and in this case the strings are, aided by the timpani); there’s a big crescendo (an increase of sound) at 27:53-27:55 – and then, rather suddenly, the sound dies away, and the last two bars of the melody are played by a lone cor anglais – a relative of the oboe, with a unique timbre, haunting and beautiful – accompanied by pizzicati in the strings.

27:58-28:13 – a piano solo. New material, quite Spanish-sounding with its guitar-like strums. I hesitate to call this a melody, as it ain’t quite one; but it’s a new section for sure, with new texture, mood and sound.

28:13-28:17 – aahh, that‘s pure Gershwin. A short 5-note motif is repeated twice, first played by the E-flat clarinet (a relative of the ‘standard’ clarinet, but with a higher pitch and a shriller, more piercing sound – and with a more strongly marked personality too, which I guess is why Ravel chose it for this spot) and then by a muted trumpet – a jazz instrument par excellence. Add to this a few syncopated cymbal notes and a repeated two-note motif played on the wood-block, inject a ‘blue note’ into that 5-note motif, stir a little bit – and you get the most wonderfully exotic jazz sound you could imagine. A total contrast with the Spanish character of the previous section.

28:18-28:32 – piano solo again. This time we do have a melody – a new one, and one which defies easy characterization – only by its end (28:29-28:32) does it acquire a clearer jazz character; we’ll return to it later, when it gets repeated by the orchestra towards the end of the movement. The left hand imitates the wood-block with its repeated two-note motif.

28:32-28:39 – the jazzy motif again – this time repeated three times – first played by the piccolo, and then once again by the E-flat clarinet and the muted trumpet. Wood-block and cymbals are back, but this time we get the addition of a harp playing glissandi – and it is audible this time, certainly adding to the ‘mix’.

28:39-28:55 – the melody from 28:18 once again, repeated a fourth higher, and in dialogue with a muted horn, which fills the empty spaces in the piano’s line quite beautifully (perhaps not the best word; but notice 28:44-28:46 especially, as well as the end of the section). The ending is different now, with repeated notes on the piano dying away, as it leads into a new theme –

28:56-29:14 – a new theme played by the piano, and it’s a new mood once again – that’s a lot of different material for such a short amount of time; its organization is unclear at this point, just one thing seemingly coming after another; let’s see if things get clearer later in the movement. But either way this theme with its singing quality is the first serious candidate for a second subject ( Mozart post). The theme is punctuated twice – at 29:01 and 29:08 – with some of the mood of the previous sections coming back in – the piano’s imitation of the wood-block is almost uncanny, I find; and the strings add a lush background.

29:15-29:29 – a continuation of the theme; and if before we had a moment of pure Gershwin, this whole section is pure Ravel – not a trace of jazz, but instead much melancholy or sadness perhaps, and those gentle pastel colors. Really beautiful.

29:30-29:46 – a repeat of the second subject – the theme is played by the bassoon, and the punctuation places (29:34 and 29:40) include the wood-block, cymbals, triangle and dry rolling passages on the piano besides the entire woodwind section. At 29:42 the trumpet suddenly takes over, there’s a big crescendo, a sweeping upwards passage on the piano (29:45) and –

29:47-30:01 – some action at last! Very fast passage-work with repeated notes on the piano, with the strings and the woodwinds helping a bit (you can hear the woodwinds doubling the piano each time the melody goes up). You’ll probably have noticed that this section basically consists of a short phrase (4 bars) which is repeated four times at slightly different pitches – at 29:47, 29:51, 29:54 and 29:58 – this is called a sequence, and is a very common device.

30:01-30:19 – more action. Good! Now, this entire section is a three-part sequence with two punctuating places in between:

- 30:01-30:04 – repeated notes and syncopated rhythms in the piano; the motif is taken from the main theme (you can hear that bit at 27:23) so we may safely assume we’re in the development section of the movement (again, referring to the Mozart post for explanations on the sonata form). The orchestra provides rhythmic support. A very satisfying place to play – you can really hammer out all those notes.

- 30:05-30:08 – first punctuating passage – our beloved 5-note motif repeated three times on the piano, surrounded by a long, held chord in the orchestra. (Something I forgot to mention while discussing the 5-note motif above: this music is in double meter (2 or 4 depending on whether it’s a fast or a slow section) – so by its nature a 5-note motif will skew the perceived meter, adding to the jazzy feeling. The interesting thing is, if you repeat a 5-note motif three times, you get 15 notes – but as we’re in normal 4-note bars, Ravel needs an extra note to balance things – and we get it, at 30:08, just after the end of the third repeat of the motif.)

- 30:09-30:12 – as in No. 1, just a bit higher in pitch and louder.

- 30:12-30:16 – as in No. 2

- 30:16-30:19 – as in No. 3 and louder still, but truncated in the middle, as if impatiently, and taken over by the brass for a second before moving onto the next section.

30:19-30:36 – sounds like a rhythm jam session to me (one of those ‘man, let’s get crazy’ type); not an easy place to play, either technically or rhythmically (the rhythm shifts every 2-3 bars). A short interlude at 30:26-30:28, with the horns quickly running through a part of the motif we had at 29:47.

30:37-30:45 – a descending 3-note motif establishes itself out of the chaos, and is repeated again, and again, and again (working itself into a frenzy) – first in full bar lengths (leaving the 4th note as a rest), and then, condensed, without any breaks – and joined in the end by the trumpets for extra whoomph.

30:46-30:54 – a virtuoso passage in the piano, played unisono (the two hands playing the same line, just an octave apart) – I wonder how difficult or not it is for the conductor to catch the pianist in the end (I wonder indeed, as I have to play it in three weeks; the seemingly shapeless passage is in fact studiously shaped – it’s 12 notes repeated twice, then 8 notes repeated twice, and finally 4 notes repeated twice).

30:54-31:14 – we’re back! It’s the main theme, and this section is a full repeat of 27:38-27:57, played by the orchestra together with the piano (so, the recapitulation, if you’re following the sonata form). The ending is played by the oboe rather than the cor anglais this time.

31:14-31:31 – a repeat of the Spanish theme, with more elaborate strumming in the right hand and the Tam-Tam and cymbals keeping the piano company on the downbeats.

31:32-31:39 – the jazzy 5-note motif, played this time by the piano solo, intrudes very loudly. It’s played once in normal rhythm, and then several times twice as fast (a compositional device called ‘diminution’). It dies away in the lower areas of the keyboard and connects to – 31:39-32:22 – a weird place. Remember that strange melody from 28:18? Well, this is it, just played by the harp. I say weird, because having a 30-seconds long harp solo in the middle of an 8-minutes long movement is, well, weird (but I have a feeling that weirdness is exactly what this place is about; see below at 32:29). It’s punctuated by an angelic chord in the strings at 32:06-32:10 and then continues at 32:12 as if it had all the time in the world.

32:23-32:28 – 5-note motif again, played by most everybody (the motif itself is played by the piccolo, E-flat clarinet and trumpet like before, just with a tremolo added – that’s this fluttering sound you’re hearing – the rest of the orchestra accompanies. The pwwwam in the end is produced by the trombone.)

32:29-32:59 – the horn repeats the strange theme from 31:39 – and it’s outright eerie. The horn part is written in the highest reaches of the instrument, giving it a constricted, slightly strangled sound, and it is accompanied by very fast passages in the woodwinds and lush chords in the strings – an exceptional moment in terms of orchestration, really memorable. (And I could imagine the previous occurrences of this theme being just build-up for this moment.) In the end everything dies away, and the piano starts its cadenza –

33:00-33:49 – a cadenza is a part of a concerto when the solo instrument is left alone (so, technically 27:58 is a mini-cadenza as well), usually after the recapitulation and before the coda. Ravel does something unusual here – a cadenza is usually a free treatment of various themes from the movement, combined and juxtaposed for good effect, but here the piano basically plays the second subject of the concerto in full (compare with 28:56) – just with a different texture: figurations in the left hand and trills in the right. A very beautiful texture it is, and it definitely shows off the piano (which a cadenza should do) – but structurally, we’re still in the recapitulation. Like a double function. (In truth, I find it cool, like every non-standard thing in this concerto). The melody is firstly in the middle voice (played by the left hand thumb) and then passes to the right hand after a beautiful glissando at 33:23 (that’s the pure Ravel section from 29:15).

33:49-34:13 – the orchestra joins in and doubles the piano in a repeat of the second subject – a lush, romantic, very 19th-century moment. Both orchestra and piano gradually pick up pitch, speed and volume, getting to a small climax around 34:06; from there the piano takes over with a quick downwards passage, and the coda begins.

34:13-35:02 – The build-up part of the coda is a repeat of all the material we had in the development, just in truncated form:

- 34:13-34:25 – the first part, based on the section from 29:47. There’s much tension – it starts down below, not too loudly, though full of energy which seems to be just waiting to burst. The drive is huge.

- 34:25-34:29 – the next part is based on the section at 30:01, just without the punctuating passages (we had enough of those already)

- 34:30-34:42 – this is based on 30:19 (the crazy rhythm jam session). The trumpets begin with the interlude from 30:26 (where it was played by the horns), and the piano picks up from there for even more shifting rhythms craziness.

- 34:42-34:48 – based on the 3-note descending motif section from 30:37.

- 34:48-34:56 – the piano continues with the 3-note descending motif, while the trumpet and the woodwinds alternately play bits and pieces from the main theme of the movement (in condensed rhythms, so it might not sound like it right away).

34:57-35:03 – final build-up – rising arpeggios in the piano while first the horns and then the woodwinds continue to play a short part of the main theme.

35:03-35:10 – sheer madness 🙂 you’ll keep hearing that short part of the main theme above everything, but everyone’s just trying to make as much noise here as possible (a very happy type of noise, but still).

35:10-35:12 – a descending scale to finish things off. Even there, at the very last moment, Ravel finds an opportunity for the idiosyncratic – the first four notes seem to imply a standard major scale – but the last four are from the phrygian mode (can’t explain it quickly – basically, another scale, vastly different from a major one – if anything it’s a variation on the minor one, with the second note of the scale being half-a-tone lower. It’s not important to understand that, but I’m sure you’ll notice the very strange sound of the last four notes – so this is where it comes from.).

And if we go back and look at the structure, we’ll realize there are two ways of looking at it – on the one hand, we had a long exposition, a short but distinct development, a recap with a cadenza and a coda – so, all is fine, But, on the other hand, you could say that from 27:14 to 30:54 we had a bunch of themes, motifs and sections, and then from 30:54 till the last part of the coda all of those get repeated. So, not even a binary form (which is a-b – so two different sections), but rather a-a’ (a’ meaning ‘a with variations’). Now, I’m not saying this is it (I certainly never read anything like that about this movement), but it is kinda there if you care to look at it this way. So, food for thought.

And we’re done! The first movement that is. 2nd and 3rd to follow later this week. And please kindly disregard the word ‘brief’ from this post’s title – we’re at just under 3,000 words, so brief it ain’t.

But isn’t it wonderful music?