Rachmaninov — Prélude in C sharp minor, Op. 3, No. 2, 10 Préludes, Op. 23, 13 Préludes, Op. 32

On 31 July 1910, Rachmaninov wrote a letter to his old student friend, Nikita Morozov, telling him about his compositional achievements over the summer. After confiding that he had ‘only completed the Liturgy’ (the Liturgy of St John Chrysostom, Op. 31), Rachmaninov half-seriously complained ‘that was it. Then it’s all intentions and well-meaning wishes. But the worst going is with the small piano pieces. I dislike this occupation and it’s heavy going for me. Neither beauty nor joy in it.’ Within six weeks, however, he had composed 13 such short piano pieces in rapid succession, finishing them in under three weeks. These pieces were to become his 13 Préludes Op. 32 and would complete his cycle of 24 préludes for the piano.

In this, he was following in the footsteps of Chopin, Scriabin, Bach and others who had written a series of piano miniatures in all 24 major and minor keys. He was also completing a personal journey of 18 years, which started with the composition of the immensely popular C sharp minor prélude, Op. 3, No. 2, in 1892, shortly after the 19-year-old composer graduated from the Moscow Conservatory. The cycle’s next building block, the 10 Préludes, Op. 23, wasn’t completed until eleven years later, and seven more years passed before the composition of the 13 Préludes, Op. 32. Rachmaninov’s préludes differed in size and scope from Chopin’s and Scriabin’s examples, which often were vignettes, allusions, hints of worlds; Rachmaninov’s préludes were fully developed, standalone small worlds, complete within themselves.

With so many years between the first and last prélude, the cycle became a mirror and a record of Rachmaninov’s development as an artist and a composer. In contrast to the full-hearted Romanticism of the first eleven pieces, the 13 Préludes, Op. 32 present a musical world which is much more angular, muscular and edgy. Their underlying spirit is more modern too, with only two préludes possessing the unashamed, unselfconscious Romanticism of Rachmaninov’s earlier works: the G major prélude, Op. 32, No. 5, which is pure and gentle as a summer’s morning, and the G sharp minor prélude, Op. 32, No. 12—wintry, heartfelt and personal in its mood. The divide between the two worlds is particularly striking at the transition between Op. 23 and Op. 32. The opening phrase of the C major prélude, Op. 32, No. 1, with its dense chromaticism and visceral drive, immediately shatters the complex, delicate dream woven by the G flat major prélude, Op. 23, No. 10, like the herald of a new era.

Despite this rift, the 24 préludes were clearly conceived by Rachmaninov as a single cycle, evident in the careful planning of tonalities in the two blocks of Préludes, Opp. 23 and 32. Moreover, he used an ingenious framing device, linking the very last prélude, Op. 32, No. 13 in D flat major with the very first one in C sharp minor through the use of motifs. The chromatic descending theme of the middle section in both préludes is identical but even more significant is the descending three-note motif, perhaps one of the most famous opening gestures in piano literature (a point certainly not lost on Rachmaninov, who was in effect forced by audiences to play the C sharp minor prélude as an encore after every concert). Rachmaninov uses this motif (transposed into the major) multiple times throughout the last prélude, right from the first bar, culminating in a triumphant fortissimo (track 24 3:52), lending a strong sense of closure and fulfilment.

Looking at the individual préludes, the cycle shows an incredible variety of character, colour, texture and mood. No two préludes are fully alike; even between seemingly similar ones, like the D major, Op. 23, No. 4, the E flat major, Op. 23, No. 6, and the G major, Op. 32, No. 5 (all of which feature singing, lyrical melodies over a calmly flowing accompaniment), a careful differentiation of tempo, mood and register ensures that each prélude’s character is clearly defined. I already spoke about the gentle atmosphere of the G major prélude, not dissimilar to Rachmaninov’s song Lilacs, Op. 21, No. 5; the D major prélude is richer and less fragile, with a bigger climax, followed by the melody returning in splendour one last time, as if a very wide horizon has opened up before us. The E flat major prélude is the most heartfelt of the three, the most caring and loving—and also the most inwardly excited, with a freshness to it, an awakening, a breath of fresh air. This prélude reminds me of the many great female protagonists of Russian literature, Tatyana, Natasha and others, with their tenderness and inner strength. The real inspiration, however, lay closer to Rachmaninov’s heart: ‘it really just poured out of me all at once on the day my daughter was born (19 May 1903).’

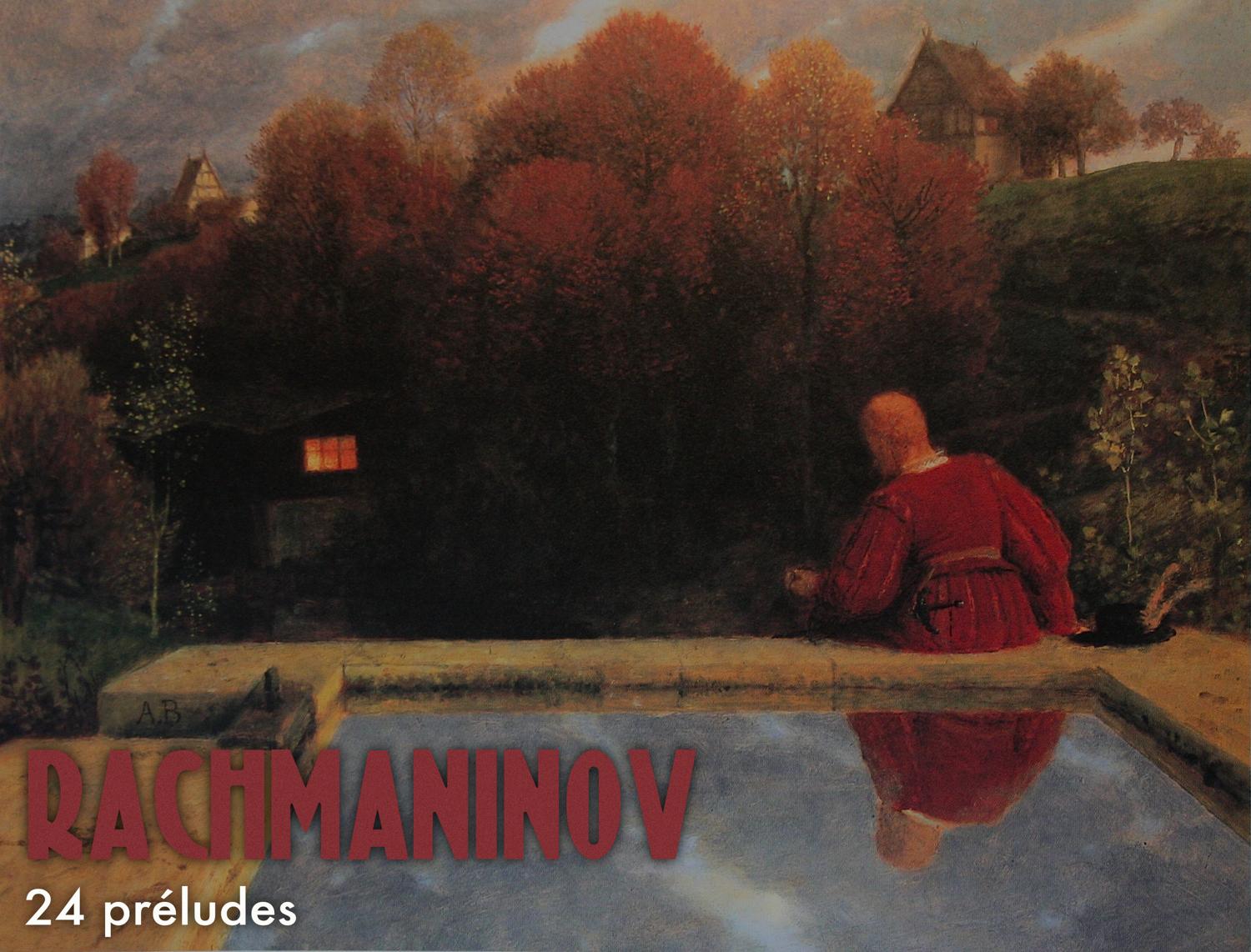

As a more literal source of inspiration, Rachmaninov said that the B minor prélude, Op. 32, No. 10 was inspired by the painting The Return or The Homecoming by the Swiss symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin. The painting depicts a man, sitting on the edge of a pond with his back to us, looking down the hill at a small house with a single lit window. The colours are autumnal, auburns, reds, and browns, with an overcast, dusky sky above russet trees. Rachmaninov’s music is the most personal interpretation of the painting imaginable. The opening mood is sombre, solemn, subdued, with the measured alternation between the melody above and the short chords below creating an almost hypnotic effect. Later comes a tremendous buildup of repeated chords supporting a heavy melody, leading to an almost unbearably painful climax. Out of its aftermath appears a dreary, lifeless, desolate landscape. Later the opening theme is reprised and leads into a coda with the sound of steps receding into the distance. The final chord is at first in a major key, only to turn to minor at the last moment.

How to relate the music and the painting? The painting itself, of course, is very ambiguous—the scene doesn’t show a happy reunion, but just the protagonist, looking down at a house, not quite approaching. The title is like a cleverly chosen catalyst, driving our imagination to explode with possible interpretations. And I think that Rachmaninov’s prélude is one such interpretation. I see it as a masterful musical portrayal of the inner world of a man, to whom the homecoming is anything but simple and obvious. We can imagine any background story we wish, but it’s obvious that the present scene evokes very painful memories or raises painful thoughts—both the tumult of chords in the middle section and the sparse barrenness afterwards seem to speak of great inner turmoil and anguish. And the coda, if indeed those are steps receding into the distance, is just as ambiguous: whether the man takes those steps to approach the house or to turn away from it, is left for each one of us to imagine, as with the meaning of the bittersweet majorminor chord in the end.

Even if we don’t know the stories behind the other préludes, their character is often clear. Elements of nature seem to be present in a few of them. The prélude in B flat major, Op. 23, No. 2, is reminiscent of Rachmaninov’s song Spring torrents, Op. 14, No. 11, which is very similar in mood and texture. The song talks about the exuberant coming of Spring and the boisterous rivers and brooks who are its messengers and forerunners. The prélude of course has no vocal part, but the middle section more than makes up for it: a melody in the tenor line is surrounded by a fully independent bass and soprano, making the piano sound like two instruments at once, in Rachmaninov’s inimitable way. Contrasting with it is the prélude in C minor, Op. 23, No. 7, which seems to depict a winter storm; mostly quiet and subdued, but flaring up to passionate climaxes. And as always with Rachmaninov, it’s never only a depiction of nature: a strong emotional undercurrent suffuses the music, giving the storm and its outbursts a very personal character.

We can also find elements of the exotic—the Scheherazade-like middle section of the G minor prélude, Op. 23, No. 5, the rhythms and melodic inflections of the B flat minor prélude, Op. 32, No. 2, which are reminiscent of the Alhambra, or the slightly bizarre harmonies of the F major prélude, Op. 32, No. 7, which is in fact written in the uncommon Lydian mode. Russian elements are there too; though rarely a folksy composer, Rachmaninov could capture the feel of a Russian fair to perfection, as in the last movement of the Suite for two pianos No. 1, in the later Étude-tableau, Op. 33, No. 6, and here in the E major prélude, Op. 32, No. 3, with its happy tumult and many bells.

Bells, an all-time favourite sound for Rachmaninov, are also the main feature of the C sharp minor prélude, so much so that it was nicknamed The Bells of Moscow by Western audiences. A special moment comes towards the very end when, over a series of gradually receding tolls in the bottom part of the keyboard, there appears a melody inside the right-hand chords: the first notes of the medieval chant Dies irae, which was to become a recurring motif for Rachmaninov, appearing in many of his compositions.

And though not at all folksy in character, the D minor prélude, Op. 23, No. 3 is for me a Russian folk or fairy tale, of the dark and earnest kind. Rachmaninov marked it ‘in minuet tempo’, and while it is certainly in 3/4 time, the character—so warm, personal, with a strong sense of narrative that reaches an almost epic breadth in the culmination—is far away from any kind of stylised dance. It’s exquisitely constructed: relatively complex in structure, but completely unified through the extensive use of the prélude’s opening five-note motif, which appears everywhere throughout the piece, whether in the melodic voice, accompaniment, or as counterpoint. It also contains an exceptional moment, when time seems to stand still, and over a long-held note in the bass there’s a series of reminiscing phrases—the selfsame opening motif repeated several times, with a strong sense of loss and grief. This passes with a return to the fairy-tale character in the coda, which ends the story.

Apart from The Return, the 13 Préludes, Op. 32 contain two other larger-scale préludes—that in E minor, Op. 32, No. 4, and the last one, Op. 32, No. 13. The E minor prélude is a war ballad, epic in mood, reminiscent of old Russian poems, such as The Lay of the Host of Igor (or of The Lord of the Rings, if one prefers). The last, the prélude in D flat major is a magnificently constructed valedictory gesture. From its quietly proud opening chords, through a mysterious middle section to the tremendous roar of the reprise and an extended coda, it is broad, victorious and life-affirming—a wonderful close not just for this prélude or for Op. 32, but for the complete cycle.

I would like to dedicate this album to the memory of my grandma, Genrietta Milman. A gifted pianist, she was one of my earliest musical inspirations, and it was under her hands that I had first heard the E flat major and G major préludes. — Boris Giltburg